- Home

- Robin Barratt

Maria's Story Page 7

Maria's Story Read online

Page 7

“Why not?” he asked and looked around at her friends who whispered and giggled quietly amongst themselves.

She didn’t know what to say.

“Come on,” he looked at her chair, “it isn’t far and we won’t be long. Can I push you?” She so desperately wanted to go with him, to feel what it was like being with a boy for the first time. Maybe, just maybe she might even kiss him.

“I can manage myself,” she said, almost confirming that she would go with him.

“But I want to,” he said. He seemed so kind, so sensitive, so reassuring. “Here, let me lift you, don’t worry,” he laughed, “I won’t drop you.”

He gently picked her up and placed her in her chair as her friends stared, silent, and dumbstruck.

“You promise we won’t be long? My sister will be back and I don’t want her to worry.”

“I promise.” He said

“Tell Nadezhda I won’t be long,” Maria said to her friends smiling as she was pushed away. They nodded and smiled and giggled excitedly and thought how wonderful it was that Maria had met a boy, and what a boy!

Sergey waved to his friends across the pavement and wheeled Maria onto the path and away from the square towards the rail track.

“Promise we won’t be long?” Maria looked up and over her shoulder, concerned yet smiling, anxious and nervous yet extremely excited.

“I promise, you can meet my friends, stay a short while, have a beer or two and I will take you back.”

She had never drunk a beer in her life, let alone two. What an evening this was going to be, she thought to herself as he pushed her nearer to the tracks and the trains.

“Where do you live?” she asked.

“In Tumen,” he said. “I work on the trains. We take freight backwards and forwards, and to other places too. I have been all over the region. All over. I am going home later, on the last train. On that train there,” he pointed towards a line of four freight carriages sitting quietly on the tracks. She wondered if she should tell him that her grandmother came from Tumen, but decided against it; she was sure he wasn’t interested in where her grandmother came from!

They left the noise and activity of the village square and made their way towards the row of carriages he had pointed at a few moments earlier. “My friends are having a few beers in one of the middle carriages. We’ll take the train and empty carriages back to Tumen tonight and we’ll fill them with goods and stuff first thing tomorrow morning and take them someplace else. It is an easy job really.” She was feeling a bit uneasy with being so far from her friends and her sister, but felt good about being with Sergey, the only boy she had ever been alone with. She sat and listened to him as he chatted about his job and the goods they transported from town to town and the fact that sometimes crates would break open and they managed to take some of the goods home. It wasn’t stealing he said, “because they broke and things fell out”. Sometimes there would be parts for cars, which he managed to sell to a local market, or wood or coal.

As they approached the carriages they could hear voices and laughter.

“Hey guys, it’s me Sergey,” Sergey called up as they moved towards the centre carriages. The third carriage’s sliding door was half open and a head appeared round the corner. “Hey, Sergey, where have you been? Who’s your friend?” he asked as he stood in the doorway.

“Maria,” he called back, “Give me a hand.”

The other boy jumped down off the carriage and together they lifted Maria out of the chair and onto the carriage. A girl appeared “Hi Maria,” she said looking down at Maria as she sat and waited for Sergey and his friend to lift her chair into the carriage. They then lifted her back into her chair and wheeled her across to the far corner of the carriage, where everyone was sitting on wooden boxes or on the floor leaning against the carriage walls. Apart from the girl that had just greeted her, Maria noticed one other girl and apart from Sergey and his friend, two other boys. Maria said hello to everyone and Sergey handed her a beer. As everyone around her chatted and laughed she stared at Sergey as he talked with his friends and drank his beer. The compartment was warm and cozy and everyone seemed friendly and kind and she was getting drunker and drunker. She had never been drunk before, nor had she ever been in such a place before. She liked the effect the beers were having, and she loved being there; listening to everyone laughing and watching as they too seemed to get drunk and noisy and less inhibited. She looked at Sergey and he occasionally looked back at her and smiled. She was enjoying every minute and she never felt better in her life. Suddenly the train jolted and moved and a wave of panic spread over her.

“What is happening?” she called out.

“We are going home,” one of the boys whose name she couldn’t remember shouted drunkenly and laughed.

“But I can’t, let me off,” she half called, half giggled through the fuzzy mist of intoxication.

“You can’t get off now,” the boy said, “We are moving,” and laughed some more. She looked around trying to find Sergey. It was dark and now very late and through the haze she just made out Sergey kissing one of the girls.

Everyone was drunk and ignoring her calls to be let off the train.

“Sergey, help me, please,” she pleaded. Sergey looked over. “Don’t worry, we will be returning shortly and we’ll let you off when we get back. There is nothing you can do now so have another beer,” and he handed her his half empty bottle. Tears were rolling down her eyes as she uneasily sipped the beer.

***

She woke up and everything around her was silent. The train had stopped. She looked around; there was nobody. The carriage was empty apart from discarded beer bottles and cigarette ends and a girl’s scarf. She looked around for her wheelchair but that was gone too. Using her arms to lever herself upright, she slowly crawled to the carriage door, which was slightly open, but not enough to get out. Wedging her small body up against the metal surround, she pushed the heavy sliding door inch by inch until it was opened just enough for her squeeze her body through. She perched at the edge of the doorway looking down at the ground about six feet below. Once more tears filled her eyes. Somehow she could sense that things were changing. She missed her sister and her friends and wanted to be back with them laughing on the grass and looking at the boys walking by. Why did she allow herself go off with him, a complete stranger? She thought about her sister and friends and wondered how they would be worrying and looking everywhere for her. She had never gone off on her own before. She thought about her grandmother who must be beside herself with worry by now. She could see her mother banging on the door of the local police station waking the sleepy and probably drunk officer in charge, demanding that a search party be sent for. There was only one policeman in her village and he had little to do, and even if he wanted to there was no way he would ever be able to summon other policemen in the middle of the night from other villages and towns nearby. And anyway, she was last seen going off with a boy. He would probably tell her mother to go back home as her daughter was sure to be having a good time somewhere and would be back with the morning sun.

She looked out of the carriage. Where was she anyway? She could see a few sets of tracks in front of her, a solitary carriage further up to her right, on another track, and forest as far as she could see in both directions.

She leaned out as far as she could and could just about make out the end of the line of carriages in both directions, but no engine. Whatever had moved them earlier that night had been detached and had disappeared. She had no idea what time it was or how long she had been asleep but she thought it might have been at least a couple of hours as it was just getting light, and mornings start very early in the summer in Siberia. She knew she had to get off the train as it might leave again and take her God only knows where, so she rolled herself onto her stomach and slowly swung her body over the edge of the doorway. Grip

ping the bottom of the door-frame tightly, she swung her body over the edge. Maria hung there for a few seconds, looked down, closed her eyes and let herself drop, screaming in agony as the stumps of her legs smashed against the hard ground below.

She lay on the ground, still, eyes tightly closed, moaning with the agony and shock of the fall. As the pain gradually subsided she slowly pulled herself up, propping herself upright with her arms. She looked around and under the train and saw a flicker of light in a clearing, between other carriages and across a few more sets of tracks. Although there was room for her small body to go between the wheels under the train, she was afraid that she might get stuck, or that the train might move, so she slowly crawled alongside the line of carriages to the end and across the tracks towards the flickering light. The ground was hard and stony and her hands soon became cut and bruised as she moved them forward a few inches, raising her torso slightly with her shoulders and swinging her body forward. She grimaced each time the ends of her bruised stumps touched the ground.

As she got closer to the flickering light she could see it was a small fire, and around the fire a group of people were huddled. Behind them stood an old dilapidated two story building. She could see the broken windows and door, half hanging on one hinge. Even though it was getting lighter, she couldn’t quite make out the exact number of people, but it looked as though there were also a few lying curled up on the floor, probably asleep. She could see, however, that they were not the group that had left her in the carriage but looked like some of the homeless she sometimes saw begging in the streets of her village. She hadn’t seen them often, as they quickly moved on, but she knew they did exist. She was afraid, afraid of where she was and of the group huddled in front of her, but she knew she had to get help and they were probably the only people that could help her. She slowly and nervously made her way towards them.

As she approached one of them looked up and stared at her. He didn’t say anything, just stared at her as she shuffled closer. He silently nodded, as though accepting she was one of them, and bowed his head again, going back into his own world.

“Hello, can you help me?” Maria whispered to no one in particular.

No one replied. No one looked up. One of them slouched drunkenly to the floor, curled up, muttered something and fell asleep. The others just sat there staring at the fire, occasionally taking sips from bottles by their side or in their hands, occasionally muttering something incomprehensible.

“Can you help me, please?” Maria pleaded, louder.

The person that first stared at her looked up and said “We can’t help anybody.” He looked back down at the bottle in his hand and took a swig.

“But I need to get home to my village, I fell asleep on the carriage, over there,” she pleaded, pointing to where she had come from, but no one was looking, “and I want to get back home, please help.”

Staring at his bottle he said quietly “we can’t help you, what can we do?”

“Where are we? Where’s the nearest village?” she said, trying to hold back her tears.

“That way,” he said pointing “About two kilometres.”

“Two kilometres!” she screamed to herself. It had taken all her energy and willpower just to crawl from the train over to where the homeless were huddled, she knew she couldn’t crawl two kilometres.

“Best you rest and see what the day brings,” he said, laying down and falling instantly asleep. She curled up in front of the dying embers of the fire and closed her eyes. Afraid to go to sleep but exhausted, she lay listening to the silence around her, hearing nothing but the crackle of the fire and occasional snores of the homeless.

***

She looked up at the clear sky and the clouds and watched as the birds swooped and squawked. She could hear her mother in the kitchen talking to her sister, she felt the familiar warmth of her apartment and smelt its recognizable smell, a smell so distinctive and comforting. She opened her eyes and stared up and watched as the clouds turned dark and filled the sky above her and the noise of the birds turned to a crunch and grind and rattle and clash of metal hitting metal.

“What have we got here?” a voice said from above as the clouds turned to a dark human shape staring down at her.

She propped herself upright, frightened, staring up at the old man standing in front of her and then around at the tracks as she saw an engine coupling the solitary carriage in the distance.

“Can you help me?” she asked urgently.

“I can’t even help myself, my dear,” he said, “but I do have some bread you can share. I don’t have much.” He handed her a small piece of bread and sat down beside her looking out at the tracks.

“You don’t look like one of us,” he said, looking at Maria’s clean and relatively new clothing and down at the recognizable stumps of her legs beneath her blue jeans.

Maria quickly told him the story and how she ended up on the carriage in the middle of the night alone.

He shrugged “Shit happens,” he said and laughed to himself, “one minute all is fine, next minute shit happens. The best thing for you to do is to try and get the attention of one of the train drivers that pick up the carriages” he nodded at the engine towing a carriage off into the distance, “and find out if anything is going back to your village, although they rarely take any notice of us. The drivers are supposed to check all the carriages before they move them, but they rarely do. They don’t care who’s on board, as we get kicked off anyway when they come to load. Then who knows where we end up!” He laughed. “The village is quite a way down there,” he pointed, and there is a phone box in the centre of the village, but mostly it doesn’t work, or so they say. Does your mother have a phone?”

Maria shook her head. She didn’t know anyone with a phone and only saw the headmistress use the phone once when she was in her office a couple of years ago, and even then she remembered that she couldn’t get through to whoever it was she was calling.

“Where do you live?” she asked.

“Here and there. Nowhere really. We may go on the carriages somewhere,” he nodded, speaking not about himself, but about the group. “Beg or steal food and, if lucky, come back here, or maybe end up somewhere else. We sometimes walk into the village, but they don’t give much, the bigger towns are the best, but it is a long walk, about five kilometres that way,” he pointed in the opposite direction. “The road is a hundred metres behind the building,” he nodded at the building, “you might be able to stop a car or a cart, but they don’t pass that frequently, one or two every hour or so. No, your best bet is to try and get the attention of an engine driver, and then he will tell you if and when a carriage is going back to your village. They pick up and drop off carriages all day. But you have to be quick.” He looked down at Maria’s stumps.

She noticed a couple of the homeless walking towards the carriages she had come from. “Where are they going?” she asked.

“They’ll be off for a lift.They will wait in one of the carriages and go wherever it goes. There’s no food sitting around here!” he laughed. She suddenly felt very hungry and quickly ate the bread.

Maria carefully tore strips from the bottom of her blouse and wrapped them around her sore and bruised hands. She also tied her trouser legs together just below the bottom of her stumps to make it more comfortable for her to move around. Her legs were sore and badly bruised but the rest of the morning she ignored the throbbing pain and crawled over the tracks towards engines that came and went, trying to shout up at the drivers who either ignored her or simply didn’t see her. It crossed her mind about placing herself in the centre of the tracks directly in front of a train, but from the way the drivers seldom looked down, or aroun,d she knew she couldn’t move quick enough before the engine would run her over, and even then she doubted that the drivers would notice. The engines were monsters compared to her little body, and she simply wasn�

�t quick enough to get to the drivers as they stopped and connected the carriages; by the time she got near them, they were on their way again. Her hands were raw and bleeding and her arms ached terribly from the lifting and swinging of her body up and down and over the tracks. Once or twice the drivers seemed to notice her, seemed to hesitate for a few seconds, only to look up and pretend the shabby looking girl with no legs was not there, or not real, or some kind of decoy for a gang to board and steal his train. Evening arrived and the engines stopped coming and going and Maria returned to the huddle of homeless sitting round the seemingly endless fire. She hoped to see the familiar face of the old man she had spoken to earlier, but he was nowhere. New faces sat, some talking, some silent, some drinking, some sleeping, but all hungry. She needed to eat too, but couldn’t bear to ask for food, not from those whom she saw and knew were desperately hungry themselves. No one asked who she was or why she was there; they came and went, each with a story to tell but no one to tell it to.

She curled up silently, desperately hungry and thirsty and thinking about her sister and mother and grandmother. She fell into a deep sleep.

“Morning my dear,” the same voice as yesterday said as she looked up. “Here, you must be hungry, take this,” and handed Maria a bottle of water, a chunk of black bread and three small apples. Her eyes lit up as she gulped down the water and stared at the apples and bread. Never in her life could she imagine the joy of being given an apple, not just one apple but three. She said nothing as she ate the bread and quickly followed by the three apples, one after another.

“Slow down little lady,” the old man said, “you might not get any more for a while.” She shrugged. She wasn’t homeless, she would be going back home soon, back to her mother and grandmother, to sausages for breakfast and soup for dinner, to the sounds of laughter, to her room and her books and her posters and her sister’s niggling yet funny ways. Soon she would be wearing clean clothes and have a hot bath and be able to clean her teeth. Soon she wouldn’t have to go to the toilet round the back of old building where others had pissed and crapped, hoping no one would see her. She wasn’t homeless.

Bouncers and Bodyguards

Bouncers and Bodyguards The Mammoth Book of Hard Bastards (Mammoth Books)

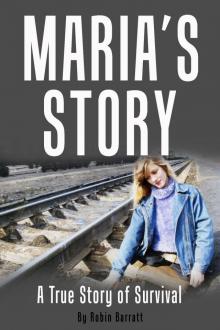

The Mammoth Book of Hard Bastards (Mammoth Books) Maria's Story

Maria's Story